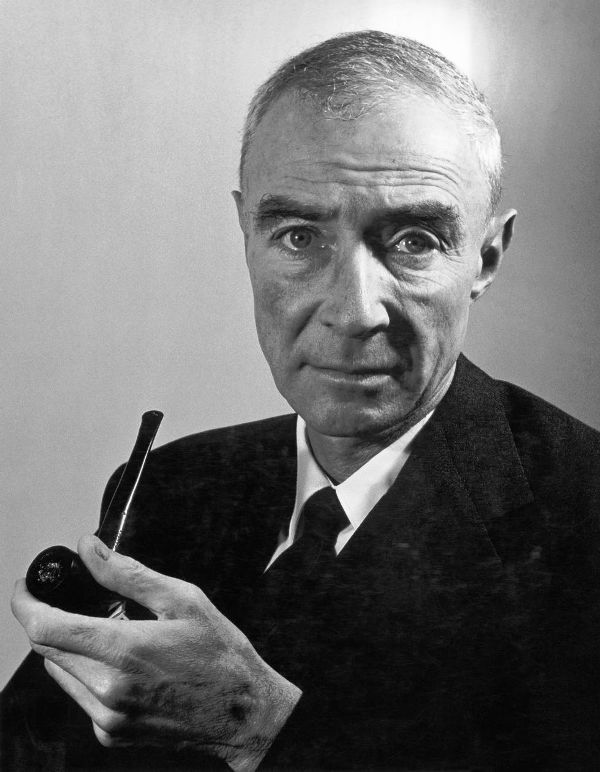

J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1067) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the head of Project Manhattan, which led to the development of the world’s first nuclear bomb. Oppenheimer earned the name “father of nuclear bombs” for his pivotal role in the development of nukes. He breathed his last on 18 February 1967 in Princeton, New Jersey, United States of America.

Contents

Wiki/Biography

Julius Robert Oppenheimer was born on Friday, 22 April 1904 (age 62 years; at the time of death) in New York City, United States of America. His zodiac sign is Taurus. Oppenheimer received his early education at Alcuin Preparatory School in New York. He joined the School of Ethical Culture Society in New York in 1911. He was a sharp student and took a keen interest in English and French literature. He completed the third and fourth grades within a year and even managed to skip half of the eighth grade.

A chilhood image of J. Robert Oppenheimer

As his academic journey progressed, he developed a liking for chemistry and mineralogy. Robert completed his schooling in 1921; however, he had to drop his studies for a year as he had to undergo treatment for colitis. In 1922, he enrolled at the Havard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he majored in chemistry. Harvard mandated the completion of courses in history, literature, and either philosophy or mathematics. He enrolled in six courses per term instead of the typical four to make up for his delayed beginning. His exceptional academic performance earned him admission to the undergraduate honour society, Phi Beta Kappa. Furthermore, due to his independent study accomplishments, he was granted graduate standing in physics, allowing him to skip foundational courses and delve into more advanced subjects. His interest in experimental physics was sparked by a thermodynamics course instructed by Percy Bridgman. In 1925, Oppenheimer completed his graduation at Harvard, earning a summa cum laude Bachelor of Arts degree.

A photo of Oppenheimer taken when he was studying at Harvard University

He attended the Christ’s College, University of Cambridge. During his time at the University, he penned a letter to Ernest Rutherford, requesting the opportunity to conduct research at Rutherford’s Cavendish Laboratory. To get entry into the laboratory, Oppenheimer asked his teacher Bridgman to write a letter of recommendation to Rutherford. Bridgman did write a letter, but in his letter, he wrote,

Oppenheimer “didn’t know one end of the soldering iron from the other.” The suspensions in the galvanometers for measuring tiny currents had to be replaced repeatedly at Oppenheimer’s own expense whenever he used the instruments.”

Rutherford, unimpressed by Oppenheimer, decided to not allow him to work in his laboratory. Thereafter, physicist J. J. Thompson agreed to accept Oppenheimer as his student; however, on one condition, i.e., Oppenheimer had to complete additional physics laboratory courses before commencing their work together. Although given the chance to collaborate with J. J. Thompson, Oppenheimer was dissatisfied during his time at Cambridge. He expressed his unhappiness in a letter to a friend, stating, “I am going through quite a difficult period. The laboratory work is incredibly tedious, and my performance is so poor that I don’t feel like I’m gaining any knowledge from it.” He further formed an unfriendly and oppositional relationship with his professor Patrick Blackett, who became a Nobel Prize winner in 1948. In 1926, Oppenheimer enrolled at the University of Göttingen in Germany to pursue his PhD. In March 1927, he completed his PhD. While in Europe, Oppenheimer released over twelve papers, which encompassed numerous significant advancements in the field of quantum mechanics. A well-known paper on the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which distinguishes between nuclear and electronic motion in the mathematical analysis of molecules, was co-authored by him and Born. It is considered to have revolutionized the way research was being conducted in the fields of quantum mechanics and nuclear physics.

Physical Appearance

Height (approx.): 6′ 0″

Weight (approx.): 55 kg

Hair Colour: Silver

Family

J. Robert Oppenheimer belongs to an aristocratic non-observant Jewish family.

Parents & Siblings

His father, Julius Seligmann Oppenheimer, was a businessman, who came to the United States of America in 1888. His mother’s name is Ella.

A photo of Oppenheimer with his parents

He had a younger brother named Frank Friedman Oppenheimer, who was a particle physicist, cattle rancher, and professor of physics at the University of Colorado. He founded Exploratorium, a museum of science, technology, and arts in San Francisco, California, in 1969.

A photo of Frank Friedman Oppenheimer

Wife & Children

His wife, Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer, was a German-American biologist. He got married to her on 1 November 1940.

A photo of Oppenheimer with Katherine and kids

His son, Peter Oppenheimer, served as a professor at the California Institute of Technology and the University of California at Berkeley. His daughter’s name is Katherine “Toni” Oppenheimer. She was diagnosed with polio as a child.

A photo of Peter Oppenheimer

A photo of Oppenheimer’s daughter

Relationships/Affairs

J. Robert Oppenheimer started dating Jean Frances Tatlock, an American politician, psychologist, and physician, in 1936, She was a member of the Communist Party USA. Their courtship, reportedly, went on even after Robert got married to Kitty. In a letter written to Major General Kenneth D. Nichols, General Manager of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, Robert claimed that the duo was about to marry twice. He also wrote that he rarely met her during their courtship. Oppenheimer wrote,

In the spring of 1936, I had been introduced by friends to Jean Tatlock, the daughter of a noted professor of English at the university; and in the autumn, I began to court her, and we grew close to each other. We were at least twice close enough to marriage to think of ourselves as engaged. Between 1939 and her death in 1944 I saw her very rarely.”

Some sources have also claimed that he was in an extra-marital affair with Tallock.

A photo of Jean Frances Tatlock

He reportedly dated several women following his breakup with Tallock. In August 1939, he met Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer and later the duo began dating one another. They continued to date each other till their marriage in 1940. He reportedly started an extra-marital affair with Ruth Tolman, the wife of his friend Richard Tolman, following the completion of his service as the director of Los Alamos Laboratory.

A photo of Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer

Religion

He followed Judaism.

Address

He resided at House number – 1967, Peach St., Los Alamos, New Mexico – 87544, United States of America.

Signature/Autograph

Signature of J. Robert Oppenheimer

Career

Professor and Researcher

Oppenheimer published his first research paper in the field of molecular band spectra in 1926; the paper presented a comprehensive approach to compute transition probabilities for the spectra. In September 1927, after Oppenheimer completed his PhD in Germany, he received a fellowship from the United States National Research Council to attend the California Institute of Technology (Caltech); however, Bridgman preferred to have Oppenheimer at Harvard. This led to Oppenheimer dividing his fellowship between Harvard in 1927 and Caltech in 1928 for the academic year of 1927-1928. He collaborated with an American chemical engineer named Linus Pauling at Caltech, researching chemical bonds. Oppenheimer’s role involved providing mathematical data, while Pauling integrated this with the chemical data. Their partnership came to an end after Oppenheimer invited Pauling’s wife Ava Helen Pauling to a meeting in Mexico. Thereafter, he worked with an Austrian theoretical physicist named Wolfgang Pauli at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH); they worked together in the field of quantum mechanics and the continuous spectrum. Later, he came back to the US from Switzerland and joined the University of California, Berkeley, as an associate professor. There, he worked with Raymond T. Birge, a renowned American physicist.

A photo of Oppenheimer taken when he was teaching at the University of California

Later, Oppenheimer collaborated with Ernest O. Lawrence, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist, and his team of cyclotron pioneers at Berkeley’s Radiation Laboratory. He assisted Lawrence and his team in comprehending the data generated by their machines, which later led to the establishment of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Reportedly, Oppenheimer’s knowledge of physics impressed Lawrence so much that he appointed him as a professor at the University; however, he demanded Oppenheimer leave teaching at Caltech. Consequently, a compromise was reached and Berkeley allowed him to be released for six weeks annually, enabling him to teach a single term at Caltech.

Oppenheimer (right) in a photo with Earnest Lawrence

Oppenheimer made significant additions to the theory of cosmic ray showers; his work eventually led to the further development of the quantum tunnelling model. In 1931, he worked with his student Harvey Hall to produce a paper on the “Relativistic Theory of the Photoelectric Effect.” In this paper, they disputed Paul Dirac’s claim that two energy levels of the hydrogen atom possess identical energy, which later turned out to be accurate. Thereafter, Oppenheimer and Melba Phillips collaborated to record the computations concerning the impact of artificial radioactivity when subjected to deuterons. In 1935, the duo published the Oppenheimer–Phillips process to discuss the effects of deuterons on artificial radioactivity. In the early 1930s, he authored a paper in which he disputed Paul Dirac’s assertions that electrons could possess both positive charge and negative energy. In his publication, Oppenheimer predicted the presence of a positron or an antielectron, a discovery later made by Carl David Anderson, earning him a Nobel Peace Prize. After Oppenheimer became friends with an American physicist named Richard Tolman, his interest in astrophysics arose. In the late 1930s, he and Tolman wrote numerous research papers in which the duo talked extensively about the properties of the neutron stars. In 1938, Oppenheimer and Tolman published On the Stability of Stellar Neutron Cores in which they talked about white dwarfs. Thereafter, he published a research paper titled On Massive Neutron Cores with his student George Michael Volkoff. Through the paper, it was shown that stars have a specific mass threshold, known as the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff limit, at which they can no longer sustain stability as neutron stars and will experience gravitational collapse. Oppenheimer and his student Hartland Snyder predicted the existence of black holes in 1939 through their research paper On Continued Gravitational Contraction. Following the publication of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation paper, these papers continued to be the most frequently referenced works by him. Moreover, they played a crucial role in revitalizing astrophysical research in the United States during the 1950s.

Oppenheimer explaining an equation as a teacher

Scientist

Project Manhattan

The Manhattan Project was a research and development project undertaken during World War II by the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. Its main goal was to develop the first atomic bomb. The project began in 1939 after the Einstein-Szilárd letter urged President Franklin D. Roosevelt to fund research on nuclear fission due to concerns that Nazi Germany might develop atomic weapons.

Beginning of Oppenheimer’s Association With The Project

In 1942, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers took over the management of the project, and in September 1942, J. Robert Oppenheimer was appointed to head the project’s secret weapons laboratory. This decision of Lieutenant General Lesley Groves, the director of the project, was seen with suspicion due to Oppenheimer’s previous ties to members of the Communist Party USA, including his former girlfriend Jean Frances Tatlock. Groves, in an interview, revealed that he chose Oppenheimer to serve in the project not only because of his in-depth knowledge of physics but also for his “overweening ambition,” which Groves thought would be beneficial for the project.

Scouting for A Place To Begin Experiments

In late 1942, Oppenheimer and Groves set out to scout for a better and secluded place, where the researchers could continue their work. While searching for a suitable location, the pair travelled to Mexico. There, Oppenheimer suggested a site he knew well, a flat mesa close to Santa Fe, New Mexico, which had formerly been the premises of the Los Alamos Ranch School. While the US Army engineers had some worries about the accessibility of the roads and water supply, they generally considered it an ideal location. They eventually built the Los Alamos Laboratory on the premises of the former school, utilizing some of its existing buildings and rapidly constructing many new ones. At the laboratory, Oppenheimer brought together a group of the most prominent physicists of that era, whom he referred to as the “luminaries.”

Los Alamos Laboratory

Oppenheimer and his colleagues were mandated to enlist in the US Army as the laboratory was supposed to be a military lab. Oppenheimer reportedly requested a direct commission as a lieutenant colonel and even purchased a uniform. However, he was deemed unfit as he was underweight, had chronic lumbosacral joint pain, and was experiencing severe coughing. The idea to enrol the scientists in the US Army was shelved after senior scientists Rabi and Robert Bacher objected. Afterwards, an agreement was made that the laboratory would no longer be under military control and instead be run by the University of California under a contract with the War Department. Oppenheimer faced challenges in managing a large project initially due to his lack of experience. However, he gradually developed his skills and became an efficient manager, leading a team of over 6,000 people. Victor Weisskopf, a theoretical physicist involved with the project, in an interview, said,

Oppenheimer directed these studies, theoretical and experimental, in the real sense of the words. Here his uncanny speed in grasping the main points of any subject was a decisive factor; he could acquaint himself with the essential details of every part of the work. It was his continuous and intense presence, which produced a sense of direct participation in all of us; it created that unique atmosphere of enthusiasm and challenge that pervaded the place throughout its time.”

Oppenheimer’s security badge’s photo taken while he was serving as the director of Los Alamos Lab

Development of Nuclear Weapon

In 1943, Oppenheimer directed the scientists working under him to begin the development of Thin Man, a plutonium gun-type fission nuclear bomb. During their study of plutonium properties, scientists stumbled upon an isotope of plutonium called Pultomnium-239. They found that despite being the purest form of plutonium isotopes, it could only be produced in small quantities. The Los Alamos Lab received its first shipment of plutonium enriched by the X-10 Graphite Reactor in April 1944. However, the scientists discovered a problem with it. The reactor-bred plutonium had a higher concentration of plutonium-240, which made it unsuitable for use in a gun-type weapon. In July 1944, the design and development of Thin Man was shelved in favour of an implosion-type weapon. In August 1944, he made a structural reorganisation of the Los Alamos Lab for the speedy design and development of a nuclear bomb. In February 1945, his team successfully developed a nuclear bomb named Little Boy. After conducting extensive research, the detailed plan for the implosion device, known as the “Christy gadget” as a tribute to Robert Christy, one of Oppenheimer’s students, was finalized during a meeting in Oppenheimer’s office on 28 February 1945.

Robbert Oppenheimer with Lt Gen Lesley R. Groves

Testing of The Nuclear Device

The first nuclear explosion in the world occurred in Alamogordo, New Mexico, on 16 July 1945 at 5 a.m. The device that was detonated was an implosion-type device made of plutonium and was estimated to have a yield of approximately 20 kilotons of TNT. The site where the explosion took place was called Trinity, a name given by Oppenheimer. The blast created a massive mushroom cloud that reached a height of over 12 kilometres (40,000 feet) and caused an intense explosion. The heat produced by the explosion was so extreme that it melted the sand in the surrounding desert and turned it into a glassy substance known as “Trinitite.” While witnessing the effects of a nuclear blast, Oppenheimer recited a verse from Bhagavad Gita and said,

If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one.”

Brigadier General Thomas Farrell, in an interview, explained Oppenheimer’s reaction to the nuclear explosion and claimed,

Dr. Oppenheimer, on whom had rested a very heavy burden, grew tenser as the last seconds ticked off. He scarcely breathed. He held on to a post to steady himself. For the last few seconds, he stared directly ahead and then when the announcer shouted “Now!” and there came this tremendous burst of light followed shortly thereafter by the deep growling roar of the explosion, his face relaxed into an expression of tremendous relief.”

The bomb developed by Oppenheimer and his team was deployed against Imperial Japan on 6 August 1945 at Hiroshima and 9 August 1945 at Nagasaki, which claimed millions of lives.

Oppenheimer with the director of Project Manhattan, Groves, at the site of the Trinity nuclear explosion

On 17 August 1945, he received a call letter from President Harry S. Truman to meet him at the Oval Office in Washington, D.C. According to reports, Oppenheimer was deeply disturbed upon examining the consequences of the bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He confided in the US President, expressing his belief that he bore responsibility for the bloodshed caused. Additionally, he openly opposed the continued advancement of nuclear weapons. This conversation left President Truman angered who allegedly instructed his secretary that he never wanted to encounter Oppenheimer in his office again. In recognition of his role as the director of Los Alamos, Oppenheimer received the Medal for Merit from President Truman in 1946.

After Project Manhattan

Working With Educational Institutes

Information about Project Manhattan was revealed to the public following the nuclear explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 following which Oppenheimer became the national spokesperson for science. In November 1945, he left Los Alamos and went back to teaching at Caltech. Soon after, he left teaching at Calton, Reportedly, Oppenheimer had lost interest in teaching after working on Project Manhattan. In 1947, he was appointed as the director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. He was offered an annual salary of $20,000 and a 17th-century manor with a cook and groundskeeper, surrounded by 265 acres (107 ha) of woodlands. At the institute, Oppenheimer mentored many famous physicists including Freeman Dyson, Chen Ning Yang, and Tsung-Dao Lee. In addition, he introduced temporary memberships for humanities scholars like T. S. Eliot and George F. Kennan. A few members of the mathematics faculty were unhappy with the initiative as they wanted the institute to remain exclusively focused on pure scientific research.

Acheson–Lilienthal Report

Later, Oppenheimer served as a member of the Board of Consultants for the Truman Administration-led Report on the International Control of Atomic Energy. Reportedly, Oppenheimer played a pivotal role in influencing the report. His viewpoint was that the US government should not only strictly monitor the production of nuclear devices but also the mines used for unearthing plutonium.

Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)

After the formation of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), Oppenheimer assumed the position of the General Advisory Committee (GAC) chairperson. In this capacity, he held a vital role in providing counsel to the US government regarding matters related to project financing, laboratory development, and international atomic policy. He supported global arms regulation and funding for fundamental scientific research. Additionally, he tried to steer policies away from intense arms competition, which he thought was inevitable between the US and the USSR. In 1048, he was appointed as the Department of Defense’s Long-Range Objectives Panel’s chairperson. In October 1949, Oppenheimer made a recommendation to the US government against developing a thermonuclear weapon as he believed that the use of such a weapon in case of war would lead to casualties in millions. However, President Truman sidelined his recommendation and ordered the making of the weapon on 31 January 1950. In 1951, Oppenheimer consented to participate in the development of a thermonuclear weapon following the creation of the Teller-Ulam design for a hydrogen bomb by Edward Teller and mathematician Stanislaw Ulam. Talking about it, in an interview, Oppenheimer said,

The program we had in 1949 was a tortured thing that you could well argue did not make a great deal of technical sense. It was therefore possible to argue also that you did not want it even if you could have it. The program in 1951 was technically so sweet that you could not argue about that. The issues became purely the military, the political and the humane problem of what you were going to do about it once you had it.”

In the same year, he was a part of Project Charles, tasked with creating an efficient air defence system to ward off any potential nuclear strikes on the US. Oppenheimer’s tenure as the chairman of the GAC ended in August 1952. Reportedly, President Truman declined to renew his term as the chairman as he wanted “new faces” on the committee.

Serving As a Member of Military Projects

He joined Project Vista in 1951, a program focused on improving the U.S. tactical warfare abilities. While working on the project, Oppenheimer questioned the effectiveness of strategic bombardment and advocated for the use of smaller tactical nuclear weapons. The final report of Project Vista recommended that the US Army and Navy should have a more significant role in delivering thermonuclear payloads to enemy forces compared to the US Air Force. However, the US Air Force managed to have the report suppressed. In 1952, Oppenheimer penned the preliminary document for Project GABRIEL, which assessed the potential hazards of nuclear fallout. Later, he was appointed to the Science Advisory Committee of the Office of Defense Mobilization as a member. In 1952, he played a vital role in Project East River, aimed at constructing an early warning system capable of giving American cities a one-hour advance notice in the event of atomic attacks. In the same year, he participated in Project Lincoln, an initiative at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory in Lexington, Massachusetts, focused on making advanced air defence systems. His work at MIT Lincoln Laboratory led to the development of the Distant Early Warning Line, which was an integrated system of numerous radar stations in Canada and the Arctic region. In 1952, Oppenheimer led a group of five experts from the State Department’s Panel of Consultants on Disarmament. Their recommendation was for the United States to delay the scheduled first test of the hydrogen bomb and instead pursue a ban on thermonuclear testing with the Soviet Union. The rationale behind this proposal was to prevent the creation of a potentially devastating new weapon and create an opportunity for both nations to negotiate new agreements concerning their armaments. The panel also suggested that the US government should openly communicate with the public about the risks associated with nuclear war and nuclear fallout. However, due to a lack of political backing, the recommendations were sidelined by the Truman-led US government. After Dwight D. Eisenhower became the President of the United States of America, he started Operation Candor, which was aimed at informing the public about nuclear weapons, the effects of the nuclear fallout, and the arms race between the US and the USSR. By 1953, Oppenheimer’s influence reached its pinnacle due to the new government taking his recommendations much more seriously than the previous administrations did.

Oppenheimer Hearing Case

Background

Affiliation With The Communists

According to sources, Oppenheimer was on the radar of the US authorities even before he joined Project Manhattan due to his affiliation with the Communist Party USA and its members. Moreover, his family members including his wife, brother, and in-laws were a member of the Communist Party USA. It was also revealed later that his house and office were put under surveillance by the FBI.

The Espionage Saga

The FBI claimed that Oppenheimer was approached by Haakon Chevalier, a French Literature professor at the University of California and a friend of Oppenheimer, in early 1943 and had a short discussion with Oppenheimer in the kitchen of his house. In this conversation, Chevalier informed Oppenheimer about George Eltenton’s alleged actions, indicating that Eltenton could potentially share technical information with the Soviet Union. The FBI also asserted that Oppenheimer failed to report the incident to the authorities in time. When the FBI questioned him in 1946, Oppenheimer backtracked and gave different statements. He came up with several names to shield his friend Haakon.

Accused of Being A Soviet Spy

The suspicion grew further after William Liscam Borden, the former executive director of the United States Congress Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, wrote a letter on 7 November 1953 to the director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, claiming that Oppenheimer worked for a Soviet intelligence unit and had provided crucial information to the Soviet Union through its agents in the US. Even though the US government did not believe Borden’s assertions, President Eisenhower asked the FBI to investigate the claims. The government halted Oppenheimer’s “Q Clearance,” which he received during his time as the director of the Los Alamos Lab, on 21 December 1953. Although he had talked about ending his consultant contract with the AEC (Atomic Energy Commission) with Lewis Strauss, he decided against resigning and instead opted to seek a court trial to prove his innocence. Maj. Gen. Kenneth Nichols, who served as the general manager of the AEC, wrote a letter to Oppenheimer on 23 December 1953. The letter outlined allegations suggesting that Oppenheimer posed a security threat.

Charges Framed

Oppenheimer faced two sets of charges. The first set accused him of having connections with communists in the early stages of World War II and providing contradictory statements to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The second set of charges centred around his opposition to the development of the hydrogen bomb in 1949, and his ongoing lobbying against it even after President Harry S. Truman had given the order to proceed with its development.

Trial

On 12 April 1954, the trial of Oppenheimer began. The trial was presided over by a panel of three judges. The hearing focused on 24 accusations. These allegations mainly revolved around Oppenheimer’s ties to Communist and leftist groups from 1938 to 1946, as well as his intentional and false reporting of the Chevalier incident to authorities. The final accusation was related to his opposition to the creation of the hydrogen bomb. A significant portion of the inquiries at the court was directed at Oppenheimer’s involvement in recruiting his former students Ross Lomanitz and Joseph Weinberg, who were both affiliated with the Communist Party, to work at Los Alamos. He faced multiple inquiries regarding his connection with Jean, whom FBI agents observed him with even after marrying. However, Oppenheimer refuted the accusations of sharing sensitive information about Project Manhattan with her and insisted that his interest in her was purely romantic. The court interrogated Oppenheimer about the inconsistencies in his statements concerning his friend Chevalier. In response, Lieutenant General Lesley Groves, the head of Project Manhattan, testified in court, explaining that Oppenheimer’s reluctance to report Chevalier was rooted in a common American schoolboy mindset, believing that it’s wrong to betray a friend. Groves asserted that Oppenheimer was deemed indispensable to the American war effort in the Second World War, which led to no disciplinary measures being taken against him in the 1940s. Numerous prominent scientists, government officials, and military personnel provided testimony in support of Oppenheimer. This group included Fermi, Albert Einstein, Isidor Isaac Rabi, Hans Bethe, John J. McCloy, James B. Conant, Bush, two former AEC chairmen, and three former commissioners. Additionally, Lansdale, who was involved in investigating Oppenheimer during the war, also testified on his behalf, asserting that Oppenheimer was not a Communist and described him as “loyal and discreet.”

Decision

On 27 May 1954, the panel of judges found that 20 of the 24 charges against Oppenheimer were either true or partially true. The judges also recommended revoking the “Q Clearance” given by the United States government to him in the 1940s; this marked the official ending of Oppenheimer’s association as a nuclear scientist with the US government. The board’s findings indicated that although he was against the development of the H-bomb and his lack of enthusiasm had an impact on other scientists, he did not actively discourage them from working on it, as claimed in Nichols’ letter. The board also concluded that there was no evidence to support the allegation that he was a formal member of the Communist Party. Instead, they considered him a loyal citizen. It was noted that he possessed a remarkable ability to keep important information to himself, but he had a tendency to be influenced or coerced in his behaviour during a certain period. In connection with Chevalier, the panel noted that Oppenheimer’s connection with Chevalier was deemed unacceptable within the security protocols for someone who typically accesses highly classified information. They asserted that Oppenheimer’s behaviour displayed a significant lack of respect for the security system’s regulations. Additionally, they noted that he was vulnerable to influence, which could pose grave consequences for the country’s security interests. Evans, one of the panel’s judges, advocated for the restoration of Oppenheimer’s security clearance. He highlighted that during the AEC’s clearance of Oppenheimer in 1947, most of the charges were already in their possession. Evans argued that it would be inappropriate in a free country to deny him clearance based on what he was previously cleared for, especially considering that he is now less of a security risk than he was back then. He also asserted that Oppenheimer’s association with Chevalier did not signify disloyalty and that he did not obstruct the development of the H-bomb.

Aftermath

After learning about the court case against Oppenheimer and the removal of his security clearance, the scientists who worked with him on Project Manhattan wrote a letter to the AEC. In this letter, they conveyed their support for Oppenheimer and conveyed their dissatisfaction with the AEC’s actions.

A photo of the letter containing signatures of the scientists who served under Robert Oppenheimer

Despite getting his name cleared in May 1954, the AEC did not reinstate his security clearance. According to sources, on 12 June 1954, Kenneth D. Nichols penned a letter to the AEC, advising them against a particular action. Within the letter, he expressed doubts about Oppenheimer’s reliability due to his association with Communism, despite not being affiliated with any political party. Nichols also criticized Oppenheimer’s actions, labelling them as “obstruction and disregard for security,” which demonstrated a consistent lack of concern for a sensible security system.

Reversal of The 1954 Decision in 2022

United States Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm declared the 1954 decision null and void on 16 December 16 2022, stating that it had been based on a flawed process. She also confirmed Oppenheimer’s loyalty and said that his clearance should have been reinstated after he was proved innocent by the court of law.

Awards

- Medal for Merit from President Harry S. Truman (1946)

- Enrico Fermi Award and a cash prize of $50,000 by the President of the United States (1963)

Oppenheimer receiving the Fermi Award in 1963 for his role in Project Manhattan

Death

J. Robert Oppenheimer passed away due to Laryngeal cancer at Princeton, New Jersey, on 18 February 1967. According to sources, Oppenheimer was diagnosed with cancer in 1965 for which he underwent chemotherapy.

Facts/Trivia

- His friends and colleagues affectionately referred to him as Oppie.

- Oppenheimer was a polyglot, and he was fluent in speaking and reading many languages including Greek, Latin, French, German, Dutch, English, and Sanskrit.

- Oppenheimer exhibited academic excellence since childhood. When he was 12 years old, he was wrongly identified as a professional geologist and received an invitation to deliver a speech at the New York Mineralogy Club.

- Once Oppenheimer finished his studies at Harvard University, he developed a keen fascination for Hindu sacred texts. Among them, the Bhagavad Gita captured his attention the most. This interest had a profound impact on him, to the point that he began incorporating quotes from the Bhagavad Gita and Meghaduta into his interviews as a scientist. In a letter to his brother Frank, he expressed how much he admired the Gita, describing it as “incredibly captivating” and the “most exquisite philosophical song ever composed in any language.” He named his car Garuda. In an interview, Isidor Rabi, a scientist who worked closely with Oppenheimer, said,

Oppenheimer was overeducated in those fields which lie outside the scientific tradition, such as his interest in religion, in the Hindu religion in particular, which resulted in a feeling for the mystery of the universe that surrounded him almost like a fog. He saw physics clearly, looking toward what had already been done, but at the border he tended to feel there was much more of the mysterious and novel than there actually was … [he turned] away from the hard, crude methods of theoretical physics into a mystical realm of broad intuition….”

- At Cambridge University, he formed a bad relationship with his teacher Patrick Blackett. Based on Oppenheimer’s friend’s account, he confessed to placing a toxic apple on Blackett’s desk once he was caught. Consequently, Oppenheimer’s parents stepped in and convinced the university not to take legal action or expel him. Instead, he was placed on probation and mandated to attend regular sessions with a psychiatrist in Harley Street, London.

- Oppenheimer was a hyperactive student. While pursuing a PhD under Max Born, Oppenheimer’s classmates submitted a petition to Max in which they had threatened to boycott the classes if Oppenheimer was not asked to stop disturbing the class during lectures.

- Oppenheimer consumed alcohol, and he used to drink whisky and gin.

- Oppenheimer was a chain smoker. It was reported that throughout his lifetime, he many times contracted minor cases of tuberculosis due to his smoking habits.

Oppenheimer with a cigarette in his mouth

- He was a trained horseback rider and owned two horses named Chico and Crisis.

A photo of J. Robert Oppenheimer with his horse Crisis

- While serving as the director of Los Alamos Lab, he was approached by a scientist who suggested utilizing radioactive material created in the lab to target the Germans. However, Oppenheimer declined the proposal and asked the scientist to only discuss the idea if he could obtain a sufficient amount of radioactive material to potentially eliminate over a million people.

- In 1948, during an interview with TIME magazine, Oppenheimer discussed his involvement in Project Manhattan and cited a verse from the Bhagavad Gita, saying, “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

- Oppenheimer was an aesthete and owned art created by notable artists such as Cézanne, Derain, Despiau, de Vlaminck, Picasso, Rembrandt, Renoir, Van Gogh, and Vuillard.

- Reportedly, Oppenheimer named the nuclear blast tests in 1945 “Trinity” in memory of Jean Tatlock.

- Oppenheimer shared a close bond with Albert Einstein, who spoke in favour of him during the 1954 security hearing.

A photo of J. Robert Oppenheimer with Albert Einstein

- According to reports, Oppenheimer was a member of numerous organizations and unions that were under Communist influence, including a teachers’ union in the United States.

- In 2023, a Hollywood film titled Oppenheimer, based on his life, was released. In the film, actor Cillian Murphy portrayed his role.

Actor Cillian Murphy in a still from the 2023 Hollywood film Oppenheimer

Categories: Biography

Source: vcmp.edu.vn